By: James J. Nolan, former Wilmington police lieutenant who is now a professor in the Department of Sociology & Anthropology at West Virginia University and a board member of ACLU Delaware.

Recently, the ACLU of Delaware filed a class action lawsuit against the city of Wilmington to address patterns and practices of unconstitutional policing by the Wilmington Police Department (WPD). Specifically, the police-probation teams known as Operation Safe Streets (OSS) were identified for constitutional violations and for racially biased policing practices. After the lawsuit was filed, The News Journal ran an opinion column recommending reforms at WPD. These recommendations seriously miss the mark. Specifically, they ignore the primary reason why OSS and other aggressive law enforcement strategies seem logical to the police in the first place. I am referring to the law enforcement mandate.

In the early part of the twentieth century a progressive movement led by police leaders rebranded the police profession as “law enforcement.” This shift narrowed the focus of American policing to social control of those deemed deviant, threatening, or undesirable via law enforcement—i.e., the law enforcement mandate. Today, we know so much more about the social, economic, and environmental roots of crime and violence. However, the law enforcement mandate ignores all of this. Instead, it sets in motion a game with a scorecard that focuses on arrests, citations, stops, searches and seizures as measures of success. This game gives rise to a law enforcement identity, an authoritarian disposition, and a world view that has white, Black, male and female police officers doing the same violent, discriminatory, and counterproductive things.

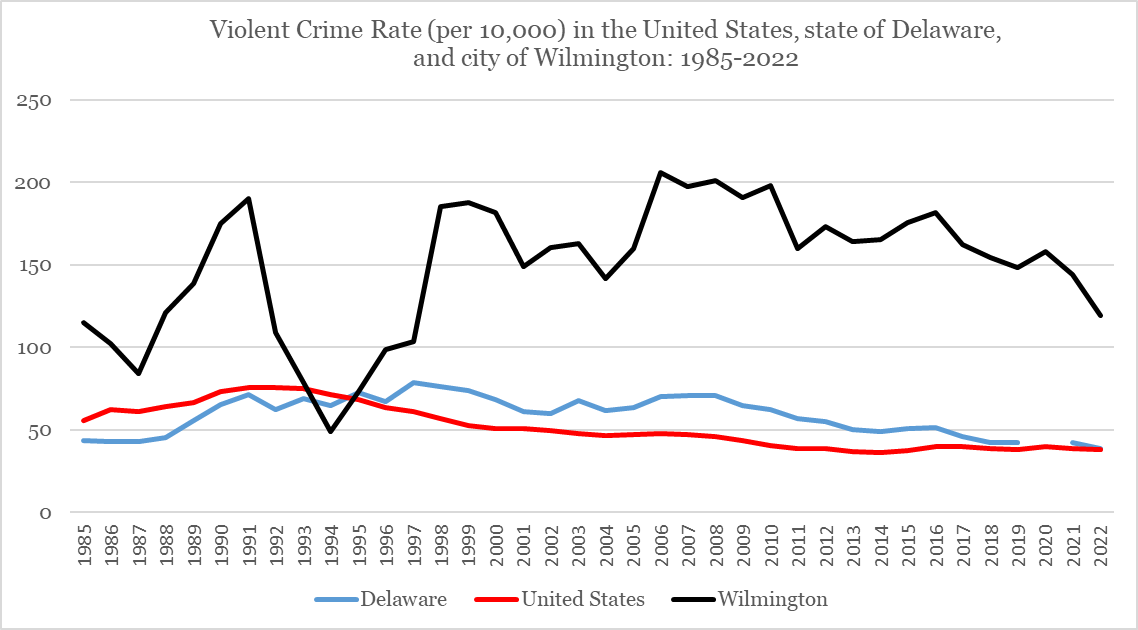

Wilmington is one of America’s most dangerous cities. When violent crime in Wilmington does decline a little, it is hard to notice. It is also difficult to give credit to the WPD playbook, because Wilmington’s violent crime trends since 2006 are so similar to those of Delaware and the United States, albeit at much higher rates.

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation

WPD maintains legitimacy through public relations and national law enforcement accreditation. Neither of these things put WPD on the path to reform. Officers continue to make lots of arrests, which is what the department recognizes and rewards as distinguished service. According to the FBI, over the past ten years, the Wilmington police arrested 35,560 people. This number is equivalent to 63 percent of all Wilmington residents age 5 to 65. Nearly half of all these arrests were related to social control. Social control arrests include crimes such as drug and alcohol violations, disorderly conduct, vagrancy, failure to obey the command of a police officer, loitering, and violations the FBI calls “crimes against society.” Still, this large number of arrests does not equate to high crime clearance rates. For example, during this same period, 57 percent of violent crimes, 83 percent of burglaries, 72 percent of robberies, and 66 percent of homicides went unsolved. Moreover, the racial discrimination in arrests is shocking. Black Americans were arrested in Wilmington at a rate nearly 3 times higher than white. For social control crimes like marijuana possession, the rate is 5 times higher.

The law enforcement mandate has not worked to keep Wilmington safe, and in fact has led to many communities being less safe and less prosperous because law enforcement targets and surveils them disproportionately. The most recent research on neighborhood safety finds that crime, violence, drug abuse, civil disorder, fear, and many other social problems all arise in places where residents are at odds with the police or alienated from their neighbors. The opposite is true where residents are cohesive, willing to pitch in and trust the police to help. With this in mind, we developed an approach called situational policing. It sets the strong, safe neighborhood ideal as the desired end for all police activity. As a new police mandate it would set in motion a different game, one that requires less controlling, coercing, arresting and seizing and more organizing, mobilizing, coordinating and cooperating.

The ACLU of Delaware took important steps to stop aggressive and discriminatory police practices in Wilmington. Such lawsuits are necessary to provide relief to communities whose day-to-day reality is affected by constant fear, violence, and disrespect from the police. However, the law enforcement mandate that makes these violent practices logical in the first place remains intact. This is the root cause of systemic police violence and discrimination in Wilmington. Only by changing this mandate can a new game emerge, one that focuses on improving the conditions in local neighborhoods so that crime, violence and other social problems will fail to thrive. This kind of approach is likely to keep communities and the police safer, while also attracting a larger and more diverse pool of applicants to the profession.